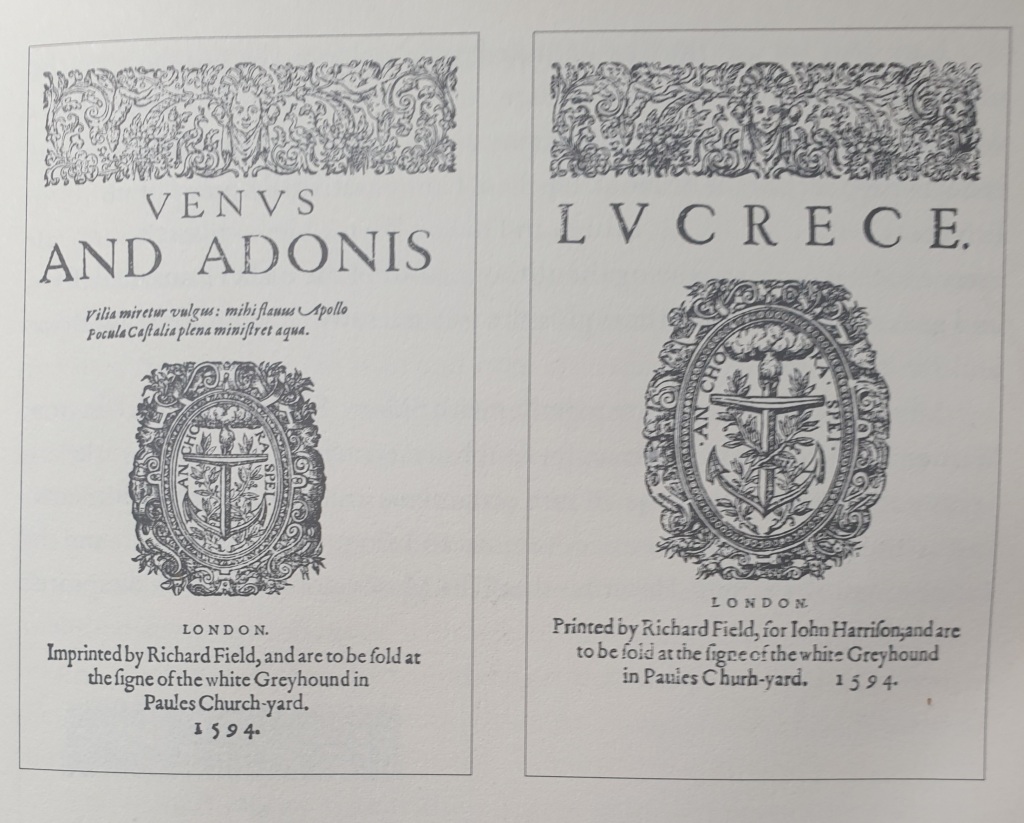

This is a rather niche or complex subject matter and rarely discussed or analysed by scholars and academics of “William Shakespeare” but assuredly worth of some mention in order to deduce the prevailing use of signs and symbols in the Elizabethan era. The most important compendium of signs and symbols can be found in “Emblemes”, illustrated by George Withers. In a previous article “Masonic Ciphers and Symbols in Shakespeare” I examined the numerous Masonic symbols and signs encoded within Shakespeare’s literary endeavours, what they meant and why they were employed and by whom. Among the sub-categories of literary symbolism was the use of the ‘Rebus’ belonging to one particular institution, person, family, trade or commercial enterprise which figuratively or phonetically is a coded substitute for the signifier to identify its owner. The pictorial or figurative emblems or trademarks are another means of identifying an author, printer or publisher and appears to be a remnant or vestige of the talismans found on coats of arms, heraldic devices, flags or monuments. In both the first print of Shakespeare’s “Venus & Adonis” and “The Rape of Lucrece” for example are found the Anchor, an emblem employed by the printer Richard Field identifying his printing and compositing work as thoroughly reliable and steadfast. Generally speaking, the anchor was a symbol of solidity, tranquillity and faithfulness suggesting also a means of holding fast to something that might be subject to confusion, disruption or instability. Moreover it was a symbol denoting “Hope” in the face of the storms that erupt in the ‘ocean of life’, viz; St. Paul insisted that “one must anchor one’s soul to Jesus Christ as the only hope of salvation”, the subliminal image being a ‘cross’ at the top (Tau) and a crescent moon (C) at the bottom. It was often combined with the dolphin or an entwined serpent which would have altered, albeit semantically its encrypted meaning. The dolphin being a sea creature was known to appear whenever storms were imminent at sea and the serpent as we may know signified ‘wisdom and regeneration’.

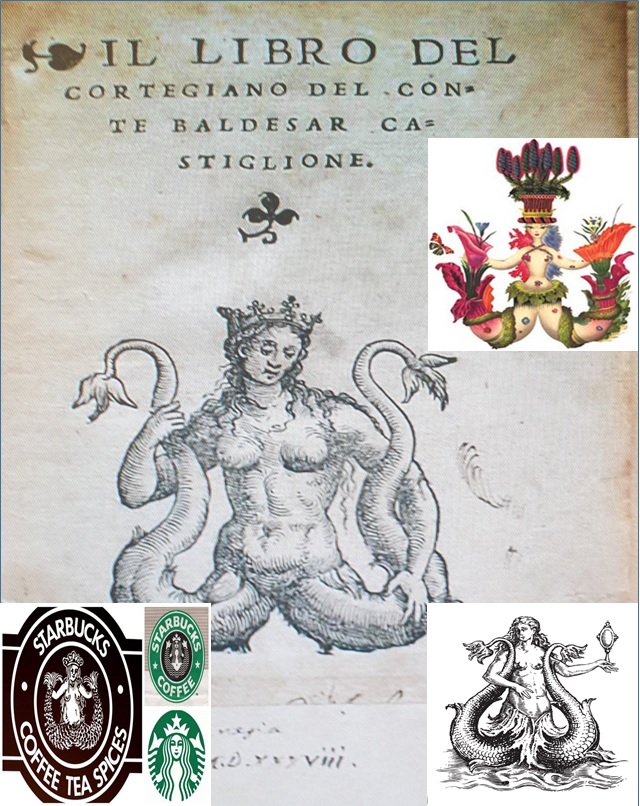

Many of these emblems seem innocent enough and inconspicuous but reveal a great deal about the authenticity of a work of literary excellence and its authentic or general provenance. They were a form of ‘branding’ and might be found somewhere in the opening title page or as headers between each chapter or section. Like many other poets and playwrights Shakespeare’s publications are rife with headers and title pages with neat and minutely decorated engravings, or woodblock engravings since that was how visual or decorative motifs were executed in print between the 15th and 16th centuries. Before we go on to discuss these emblems of Shakespearean publication it would be a useful exercise to look at a book of Italian origin which Shakespeare would have surely read and regularly referenced in his own plays and poetry; this was Baldasare Castiglione’s “Book of the Courtier” and is an excellent starting point going forward into the entire corpus of emblems, signs and symbols employed during the great Literary Renaissance in England and Europe. In his book “The Lost Symbol” the fictional author, Dan Brown suggests that the ‘Illuminatti’ or Freemasons were likewise using certain symbols as an alternate secret language, thereby communicating a secret message for present and future generations of its members. This is certainly true of Castiglione’s book which features a crowned mermaid with two tails which could be none other than the mermaid Melusine of whom many myths, legends and tales were told in antiquity. An entire book could be written about this legendary creature who dates back to the early Italian and French crusaders in the Holy Land. Though Melusine is most often thought of as a mermaid or siren, she bears a double serpent’s tail in her original form. Just as the Leanan Sidhe is a dark faery muse who bears her gift of inspiration with the price of sorrow, therefore Melusine represents the gift of “crippled genius”. She could be easily compared to a mermaid or a siren as she is sometimes depicted with the tail of a fish and is often winged and wears a crown of flowers (signifying earth, sky and water).

The depiction of mermaids and mermaid lore was popular from 1387 when her story was retold by Jean d’Arras in his “Chronique de Melusine” in “Le Noble Hystoire de Lusignan”. In this tale she is depicted as the cursed French Countess of Lusignan and reputed to be the daughter of the fairy Pressina and an ancient Scottish King. As a punishment for attacking their father, Melusine and her sisters are cursed by their mother with changeling deformities. In the d’Arras tale, Melusine is transformed every Saturday into a hideous monster with a serpent’s tale and her descendants must also bear this curse. If she were ever to be seen in her changeling form by mortal eyes, the curse would be eternal and she would never be able to obtain the release of death.

In the medieval French version of the tale, count Raymond de Lusignan, meets a strange and beautiful fairy woman by a fountain in the forest and becomes enchanted by her. She agrees to be his bride on the condition that she must be alone every Saturday, that no one must see her and that he must never ask why. Being besotted he naturally agrees and Melusine arranged to have a beautiful chateau built for them as their official residence. She bears him many children but the children are a little strange in their appearance, all of them changelings with some part of them resembling an animal, despite these strange deformities they also seem to be unusually talented in a particular craft. However, in spite of their peculiar appearance, their father loves them and overlooks their deformities in favour of their creative talents. However, the gossips at court would not let well enough alone. Raymond is encouraged to grow suspicious and jealous of his mysterious bride who never seems to age and who bears him such strange gifts. One fateful Saturday, thinking he will find her in the company of a lover, he peeks into her chambers. There he sees her alone splashing about in her bath with a silvery mermaid’s tail instead of her long pale legs. Raymond, who is both relieved of his suspicions and troubled by his discovery, says nothing to Melusine. He fears the consequence of breaking his promise but his children now frighten him and he begins to blame their strange behaviour on Melusine‘s changeling form. He is beside himself with despair and he accuses her of tricking him, of being a temptress in disguise. When she realises that he has broken his vow, she disappears without a word. Throughout the ages, the immortal fairy serpent watched over her descendants from afar and when disaster or death threatened them, she would give a warning by shrieking three times, thus she echoes the Celtic Bean Sidhe. She inspired works of art which were defective in some way, caused mysterious buildings to be erected overnight by workmen who vanished without a trace in the morning. Unfortunately all of the buildings all had some defect in their construction. She is intuitive genius and intuition that is both creative and marvellous but that is also maimed and maligned. In another sense it is the grit in the oyster that over a long period of time creates the beautiful, luminescent pearl.

In French mythology, Melusina, or Melusine, was a water-sprite related to the “Dames Blanches” (the white ladies). The Melusina legend became extremely popular during the middle-ages, especially in the northern regions of France. Melusina was a cherished figure among French noblemen and members of the royalty; some individuals even boasted of being directly related to her. In the early 1500s, Jean d’Arras, a French historian, received orders from the Duke of Berry to record all the information he could gather on Melusina. Jean d’Arras spent a number of years researching and collecting material for his major work, “Chronique de Melusine”. Much of his research was indebted to William de Portenach‘s previous chronicles on the history of Melusina. Portenach’s manuscripts no longer exist; therefore, “Chronique de Melusine” is the oldest surviving written text on the Melusina myth. In 1478, Arras’s other work, “Le Liure de Melusine en Fracoys” was published posthumously. Arras’s work added to the popularisation of the myth and, after his death, numerous versions of the Melusina myth were published in different languages, including German, Dutch, Spanish, Danish, Swedish, and Italian (for a detailed list of these works please refer to Sabine Baring-Gould‘s chapter on Melusina, in “Curious Myths of the Middle Ages”). According to Baring-Gould, the structure or the framework of the Melusina story is based on a mythical archetype involving mortal men and supernatural women. The general framework can be broken down as follows:

A mortal man falls in love with a woman of supernatural origin.

She consents to live with him, subject to one condition.

He breaks the vow and loses her.

He seeks her, and a) recovers her; or b) never recovers her.

The Melusina myth fits into this model with one relevant extension: Raymond never recovers Melusina. Popular European fairy tales, such as “Undine” written by Lamotte Fouque, and “The Little Mermaid” collected and published by Hans Christian Andersen (now a recent movie by the Disney Corporation), possess many characteristics of the Melusina story and can be viewed as variations on the myth. In “Undine” a young knight falls in love with a water fairy, Undine, and asks her to marry him. He promises Undine that he will never leave her; however, the young knight falls in love with another, a mortal woman, and as a result abandons Undine. Undine is heartbroken and, on the eve of the young knight’s wedding to his new love, she comes to him in his sleep and kisses him to death. In “The Little Mermaid,” a mermaid saves a prince from drowning after a shipwreck and falls madly in love with him. She decides she wants to be a mortal with legs in order to be near him and the human world. The little mermaid makes a deal with a water sorceress by which she gains legs but suffers from excruciating pain when she walks. She also has to give up her beautiful voice and is unable to speak. In her human form she becomes the Prince’s constant attendant, yet he never falls in love with her since she is not unable to talk to him. He eventually marries another human princess, and subsequently the little mermaid is left heartbroken and desolate. In the end, the little mermaid decides to leave the prince and returns to the sea as a water sprite. But what is peculiar is that the emblem of Melusine in rather a provocative pose was taken up later by the Starbucks Coffee Chain as their advertising logo.

Baring-Gould contends that the Melusina myth finds its roots in Celtic mythology where Banshees are female spirits who linger around certain households, lamenting and wailing when someone in the family is about to die. In French mythology, the “White Ladies,” or “Les Dames Blanches”, have some of the same characteristics as the Irish Banshees; therefore, it is possible that the Melusina myth originated in Ireland, was carried over time to the northern regions of France, such as Normandy and Brittany, and was gradually assimilated or acculturated into local French myths. Baring-Gould argues that no figures from other myths correspond as closely to the Banshees as do the White Ladies of French mythology.

The “White Ladies” were primarily associated with the Normandy region in France. The French believed that these fairies crowded the forests of Normandy and lurked near streams, bridges, and ravines, where they would accost or haunt any lost travellers. The White Ladies were generally known as being irresistibly beautiful, yet they were also cruel and furtive. They stopped travellers and forced them to dance or to answer their cryptic riddles. If travellers refused to dance, or if they gave wrong answers, the White Ladies would torment them, and afterward toss them into ditches. Melusina and her sisters qualify as “White Ladies”, yet unlike the White Ladies they were friendly and helpful to lost wayfarers. The White Ladies also functioned as intermediaries between the living and the dead, and as a result possessed abilities to foresee the deaths of humans. Like the Celtic Banshees, the White Ladies warned mortals of imminent deaths in families by lingering outside homes, weeping and wailing.

According to Baring-Gould, another source for the Melusina myth can be traced back to the mermaid or merman figure found in ancient art. Ancient civilisations, such as the Egyptians, the Babylonians, the Assyrians, and the Chaldeans, all seem to have their own version of the mermaid or merman figure. Archaeological excavations of all these civilisations have revealed engravings on stones of mermaid-like creatures not unlike Melusine. However, it is difficult to pinpoint the genesis of these creatures; the repetition of this phenomenon does suggests somehow that these stories and myths travel across countries and continents, and along the way are modified or altered to fit the needs of the culture at hand. The Melusina myth can, in a simple manner, be viewed as an amalgam of Celtic mythology with a number of other ancient myths. The Celtic diaspora extends to Asia, Africa and the North American continent. One of which appears to be of Phoenician origin, Atargatis or the Babylonian ‘she-dragon’ Tiamat or Syrian Ishtar or Astarte. It would appear therefore that an in-depth study of these emblems can reveal a great deal about the culture, beliefs and practices of historic races and their customs and traditions.

Venus & Adonis (1593):

The plague arrived in 1592 and soon after appeared the first attempt of poetry a year later when Christopher Marlowe had been brutally murdered by Ingram Frazier (See related essay; “Who Killed Christopher Marlowe”). Printed by Richard Field and published by John Harrison. The title page of Venus & Adonis features a decorative header similar in style to the 1623 Folio except that the peacocks are perched on either side of Dionysus on the stems of foliage, and either side are two cherubs gazing inwardly. Richard Field’s emblem of an anchor in an oval boss takes centre page. (See the entire essay on “Shakespeare’s Poetry”) Some commentators and researchers on the subject have asserted that the figure is synonymous with the English ‘Green Man’ legend or belief but it is fairly certain that the Greek and Roman pantheon was the most likely source for the central figure on the title page. For example the title pages and engraved portrait in the 1623 Folio of plays which for some time has been presumed to be of “William Shakespeare” reveals even more cryptic and secret messages. (See “The Droeshout Portrait” and “The Many Faces of Shakespeare”) Ostensibly this throws a great deal of doubt over the authorship of Shakespeare and points towards an aristocrat, namely Edward de Vere being the secret author of Shakespeare’s canon.

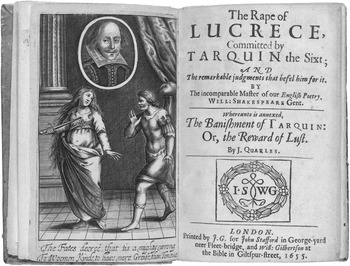

Lucrece (1593-94):

These illuminating and imaginative poems were written some 13 months after Venus & Adonis and originally entitled “The Ravyshment of Lucrece” although the first quarto displays only the word “Lucrece” on its title page. Around this time the plague was raging about the streets of London and Shakespeare was able to avoid this miasma because he was safely ensconced in the comfortable cordon sanitaire of the Earl of Southampton’s House in Holborn. Evidence suggests he might also have produced some elements of Lucrece in Lord Titchfield’s country seat in Hampshire. Edward de Vere’s alternative secret literary hideaway was Bilton Manor near the Forest of Arden and Fisher’s Folly (1584) on the Thames. The manuscript was entered into the stationers register on 9th May 1594, the following link will access the full article on this subject “The Rape of Lucrece”.

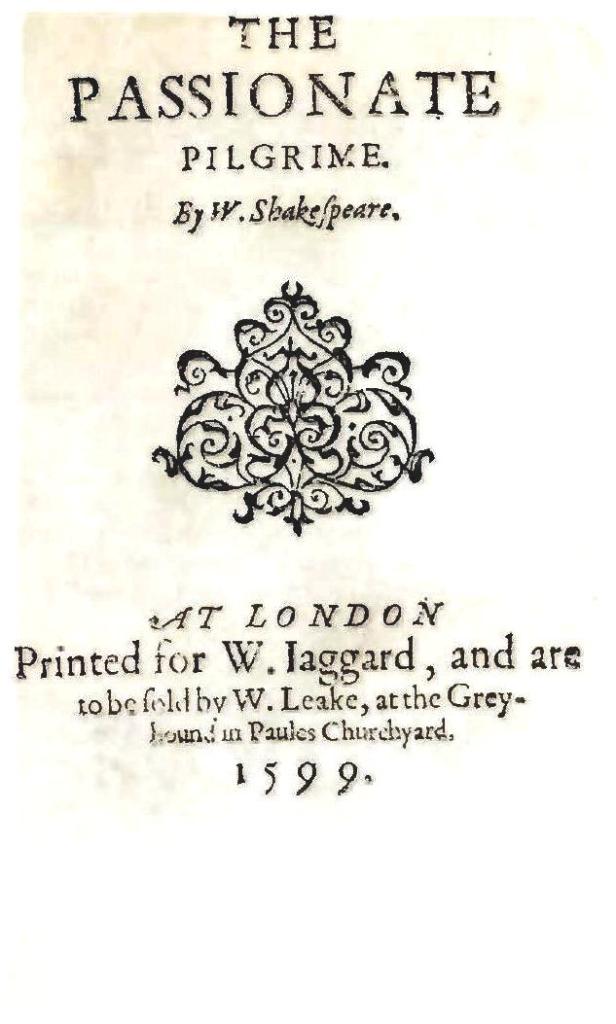

The Passionate Pilgrim (1599):

The Passionate Pilgrim was a mysterious collection of poems (138 & 144) that first appeared in print (Thomas Thorpe) around 1599 and were then criticised by Francis Meres as “sugared sonnets” in his book “Palladis Tamia”. Where Thomas Thorpe had acquired these extracts is uncertain but he probably sought to benefit financially from their printing and publishing, possibly without the author’s consent. This edition actually contains extracts from Act IV of “Love’s Labours Lost” as well as several renderings by other lesser known poets. Shakespeare and Thomas Heywood had not given their permission for one of these privately circulated editions, containing five of the sonnets along with the latter’s “Trois Britannica”, (printed by William Jaggard) and evidently voiced their displeasure (viz: “Apology for Actors”). In later editions the printer saw fit to remove Shakespeare’s name from the title page. Now consigned among the poetic apocrypha it contains the oft quoted lines (sonnet 12):

Crabbed age and youth cannot live together:

Youth is full of pleasure, age is full of care;

Youth like summer morn, age like winter weather;

Youth like summer brave, age like winter bare.

Youth is full of sport, age’s breath is short;

Youth is nimble, age is lame;

Youth is hot and bold, age is weak and cold;

Youth is wild, and age is tame.

Age, I do abhor thee, youth, I do adore thee;

O! my love, my love is young:

Age, I do defy thee: O! sweet shepherd, hie thee,

For methinks thou stay’st too long.

The second verse is a variant of Sonnet #144 which suggests it might have been pirated from someone unknown to the printing trade. Verse 3 appears to be a version of Longueville’s sonnet to Maria where the poet excuses his earth-bound misogyny because his love is primarily a goddess. Verse 4 is problematic in that a manuscript remains in Folger Shakespeare Library with an attribution to W.S most likely forged by J.P. Collier. Later research suggests an attribution to Bartholomew Griffin who is also the author of Verse 11. The same could be said of verses 5-7 however in verse 8 we return to an attribution to Richard Barnfield with the lines:

“If music and sweet poetry agree,/ As they must needs (the sister and the brother)/ Then must the love be great ‘twixt thee and me,/ Because thou lov’st the one, and I the other.”

Again a similar version is found in Jaggard’s Poems in “Diverse Humours” (1598). There appear to be musical and poetic references to John Dowland and Edmund Spenser. Verse 10 is free of any attribution to any known poet so we may freely assume it could have been written by Shakespeare or any other accomplished poet of the period. Verse 11 is clearly attributed to Bartholomew Griffin from an identical version in Fidessa (1596) although the subject matter refers to “Venus and Adonis”. Verse 12 is actually attributed to Thomas Deloney (“Garland of Goodwill”-1593 Stationer’s Office) but the earliest surviving print of this verse is from 1628. Several references are made by other poets to its opening line; “Crabbed age and youth cannot live together,/ Youth is full of pleasance, Age is full of care”; namely Beaumont, Fletcher and Nashe. The remaining verses 13-14 although striking have no known attribution to any author.

In Freemasonry the numbers 15 and 30 are an integral element of ancient Gnostic and Pythagorean symbolism, the images of the first 10 numbers are themselves extended into 15 separate categories (positive & negative), and the 30 Aeons are composed of 3 lists of tables, the Ogdoad (8), the Decad (10), and the Dodecad (9+3=12). The number symbolism of the Christian Mystery cults dovetails from one to another, primarily because that is the nature of sacred geometry, the symbolism of numbers and their relationship to abstract ideas, idiomatic forms and physical objects. Verse 15 is introduced to the reader on a separate page under the sub-title Sonnets to Sundry Notes of Music (see below). It extends to Sonnet 19 and ends with “Love’s Answer” (a quatrain) which has similarities to Marlowe’s own “Come live with me and be my love” (England’s Helicon-1600) which is also sung by Dr. Caius in “The Merry Wives of Windsor” (1597). Now melodious madrigals composed at the time were numbered 1-6 as mentioned in Nicholas Yonge’s “Musica Transalpina” (1588). The 20th verse in seven syllable trochaic lines has been attributed to Richard Barnfield (1574-1627) who published it in a compilation entitled “Poems in Diverse Humours” following on from “The Encomiom of Lady Pecunia”, or “The Praise of Money” printed by Jaggard’s brother in 1598 and entitled simply “An Ode”.

It begins: “As it fell upon a day,/ In the merry month of May

Which echoes the anomalous sixteenth verse of Passionate Pilgrim:

On a day, (alack the day)/ Love whose month was ever May…”

However, the poem is omitted from the second edition of “Poems in Diverse Humours” but an abbreviated version was subsequently printed in “England’s Helicon”. There is a slight resemblance to lines referring to the nightingale in Shakespeare’s own “Rape of Lucrece” (1128-48) that might have led to its false attribution to William Shakespeare. The 17th verse being different in tone is also found among Thomas Weelkes’ “Madrigals” (1597) although popularly attributed to Shakespeare it may have been written by Richard Barnfield according to Grosart (“Complete Poems of Richard Barnfield”) where it is followed by verse 20 “As it fell upon a day”. Verse 18 is even more difficult to determine or attribute to Shakespeare alone as several manuscripts survive in Folger MS with similar versions as those in the “Passionate Pilgrim”.

The Phoenix & the Turtle (1601):

First published in 1601 alongside several other sonnets (eg: “A Lover’s Complaint”), this was an allegorical elegy for a couple of birds that first appeared as appended leitmotifs alongside Robert Chester’s enigmatic “Love’s Martyr” or “Rosalind’s Complaint”, (“allegorically shadowing the truth of love”) with several additions from other poets of the period such as Marston, Chapman, and Ben Johnson. The ancillary authors which included Ben Johnson, Marston, Chapman and an unknown poet and in 1807 Shakespeare’s contribution adopted the title of The Phoenix & the Turtle. It was printed by Richard Field who also composited Venus & Adonis and Lucrece and it was dedicated to Sir John Salisbury. “Love’s Martyr” was an attempt by the obscure poet Chester at Ovidian verse coupled with chorographic, narrative and encyclopaedic material, such as the numerous plants, trees and birds which were listed that inhabited the isle of Paphos where the Phoenix eventually retires. Paphos is the birthplace of the Greek goddess Aphrodite and in this sense it is perceived by modern commentators as an allegory of royal succession, and by others as an allegory or belated tribute to the marriage of John Salisbury (the turtle) to Ursula Stanley (the phoenix) in 1586. Although the poem in its abstract symbolism may shadow allegorically more than one particular incident and aristocratic pairing from the period of its appearance. Incidentally, Lord Salisbury was in dispute at the time with the supporters of the Babington plot in his native Denbighshire. Shakespeare’s contribution seems to have enlarged on the symbolism of birds as omens in prophecy throughout this piece for several reasons.

The Phœnix is a mythical creature who, as many people know, rose out of the ashes, it remains an image of resurrection and indestructibility while the cooing Turtle Dove is an emblem of the Roman goddess Venus (Gr: Aphrodite) and represents concupiscence in matters of love and loyalty. The sole Arabian Tree mentioned in the second line is considered by some analysts to be the cedar from Lebanon although I think personally it is the date palm (phoenix dactylifera), although the real phoenix of the desert is the acacia tree. The question being; is cedar a funerary tree, are coffins made of it, is it mentioned in the bible or is it found in graveyards? The poem is so abstracted grammatically vague or simply confusing in parts that it has puzzled some literary and historical commentators on what its exact meaning and significance was. Some say it suggests Shakespeare’s attempts in the latter part of his career at some type of modern poetic form with reference to some particular event which had a more universal theme or appeal. While others say that Shakespeare was simply suffering from syphilis and his mental functioning had been impaired and that this gave the poem its distinct vagueness and grammatical eccentricities. For example in reading the piece the gender of the birds, the Phoenix and the Dove is somewhat vague. Clearly, the poem has some moral and political implications or veiled allegorical statements within it despite the disparities of grammar or symbolism it contains and one is therefore tempted to speculate which individuals the birds actually represent in Shakespeare’s circle? Incidentally, the title of the poem did not come into use until the 17th century and the opening line “Let the bird of loudest lay” was simply employed as its original title. Some critics have suggested that the Phoenix, a bird of resurrection, represents Queen Elizabeth Ist, and the Turtle-dove her principal secret lover and much later a traitorous agent of insurrection in the London riot of 1601, the 2nd Earl of Essex, Robert Devereux. It’s sad, somewhat resigned tone, almost to the point of bitter irony and melancholic despair may reflect Elizabeth’s feelings at signing Essex’s execution. It may be more than just mere coincidence that the date of publishing is the same as the insurrection in London.

The general message of the Phoenix and the Turtle seems to be “Oh, how are the mighty fallen in their mismatched loyalties and personal incongruities?” A statement that could of course apply to the Babington Plot (1561-86) devised by Anthony Babington and John Ballard where they were discovered and with Mary Queen of Scots were summarily executed. The organiser of the plot, Roberto Ridolfi (See “rrr-that’s the dog’s name”—-“Romeo & Juliet”) managed to escape to Spain unharmed but his Catholic cohort Sir William Throckmorton was executed along with Queen Mary. The threnos (sad song) at the end of this extraordinary poem may be an anonymous epitaph to just such a rather distressing event. So much so that some critics have argued that the poem was authored and attributed to Queen Elizabeth herself.

Death is now the phœnix’ nest;

And the turtle’s loyal breast

To eternity doth rest,

However, a similar impropriety and inevitable failure in allegiances occurred with the Earl of Essex and later when the Duke of Buckingham attempted to negotiate the marriage of Prince Charles to the daughter of the Spanish King in 1623. So, are we to speculate that the Phoenix represents the new age of Protestant England and the dove its loyal “matched” and often disloyal “mismatched” subjects? Could it even make reference to the disparity that existed politically between Protestant and Catholic subjects to their Protestant Virgin Queen?

Although the whole of the poem is suffused with double-meanings and ambiguity, the opening line gives us an interesting clue to extrapolate further; “Let the bird of loudest lay, on the sole Arabian tree!”. Well, the sole Arabian tree must surely be the palm-tree (as it derives from Alchemy and Hermeticism being equivalent to the Cabalists’ Tree of Life), the palm was sacred to Venus and the Sun (Apollo). Some commentators suggest it was the Masonic Acacia Tree, which when cut down regenerates easily. This seems to concur symbolically, as the image of a bird sitting in the palm of one’s hand and attempting to lay an egg is quite amusing! The palm of the hand (Gr: cheiro) is an image of human fate or destiny – that is what is given and what is received in human affairs and of course the Hand of God, that which intervenes in man’s affairs. The initial image of a call for the loudest of birds to rest on a sole Arabian tree (palm) conjures up singing birds (poets?) vying with each other to be in that “sacred palm” in order to “lay their eggs” or hatch their plots? In the second verse another bird is mentioned ie; shrieking harbinger which must be the owl, a nocturnal bird of prey sacred to Minerva, an ancient pagan goddess of war, witchcraft and foreboding. The third verse then mentions the eagle, an extraordinary feathered raptor that dominates the high altitudes and mountain slopes, this being sacred to Zeus, king of Mt. Olympus. The fourth verse introduces the loyal swan (Leda & the Swan?) coupled with a priest in surplice white. This might be a veiled reference to the strict Catholic Cistercian Order instituted by Bernard of Clairvaux of France who vehemently opposed rational theology and he later instituted the controversial order of Knight Templars which then morphed into the Trappist Order. He went on to further the accession of Pope Innocent II and set about zealously with the Second Crusade which failed and also wrote numerous hymns. Similarly, Zeus, Jove or Jupiter disguised himself as a swan in order to seduce the nymph Leda which denotes religious and filial impropriety. Then the fifth verse makes reference to the treble-dated crow, sacred to the Teutonic Odin equivalent to the Roman Saturn or Greek Chronos, lawmaker and god of time. The crow, like the raven is a scavenger and was often seen metaphorically as a bird of parliamentary discourse and synonymous with vehement interjection, heckling or incisive rhetoric. It parodies an anonymous poem of the time entitled “Court of Love” (writ: 1535, published 1561) which features sequentially lark, eagle, popinjay, robin, turtle dove, wren, throstle, peacock, and finally cuckoo. Similar analogies with the use of flowers were common subjects of the time. There seems to be an indirect reference in the first five verses that is synonymous with the five Dactyls of Greek antiquity and of Druidic lore, each finger of the hand sacred to a particular god. The thumb sacred to Mars (Minerva as a war goddess), the index to Saturn (Time & Repose), the middle finger to Jupiter (Excess & Good Fortune), the next to Apollo or Venus (Love Poetry) and the little finger to Mercury (Wit & Invention).

So, having set the scene within the first six verses the poem goes onto describe a series of events or consequences that allegorically might apply to several displaced personages from the court of Queen Elizabeth, not just one incongruous partnership that was arranged purely for convenience sake to usurp or support the crown. The tone is somewhat indifferent and often borders on sardonic and, in such ironic philosophical mood perhaps even resigned euphemistically to accept the follies and cupidity of that time in aristocratic circles and in the wider political sense. Some researchers have also suggested that this abstract set of events even mirrors the relationship Shakespeare may have had with his own patron Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton and the “dark lady” Emilia Larnier or even that undisclosed but well-known affair between Queen Elizabeth and her paramour Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester who had a nose like an eagle incidentally. Shakespeare’s patron the Earl of Southampton (Phoenix?) was also implicated in the Essex Rebellion (1601) by persuading the players of the Globe theatre to perform Shakespeare’s controversial play “Richard IIIrd” (about a deposition) in order to substantiate the insubordination being planned towards royal rule. Although Queen Elizabeth sentenced him to death, following pleas from his family, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment but after the death of Queen Elizabeth he was later pardoned and released by King James Ist in 1603.

A Lover’s Complaint (1603-4):

A Lover’s Complaint is a volume of poetry in rhyme royale probably composed between 1603-04 and printed later in 1609. It included this sonnet as an accompaniment to other sundry works, tracing a traditional literary theme composed as a lamentation of a forsaken lover, particularly in contradistinction to any foregoing works. It features an old man, an abandoned maid and a younger man. It was probably written around the same time as the play “All’s Well That Ends Well” because the male character in the poem resembles Bertram in that play. The presence of compound words and inventive vocabulary has confirmed it to be Shakespeare’s attempt to throw a challenge to Edmund Spenser. However, the style is very archaic, conventional and obliquely structured in contrast to Shakespeare’s much later experimental poetic styles found in for example “Venus & Adonis”, or “The Rape of Lucrece”. It takes the form of an hysterical maid describing her heart-felt grief at being abandoned by a lover to a shepherd, who leaves off grazing his flock, to listen to her tearful confession. It employs the rhyme royale (ABABBC) to communicate her perplexity at her lover’s cruelty and faithlessness. It may be that this collection was the outcome of a poetic sketchbook that would have been used to stretch the author’s skill in preparation for a theatrical production. There are significant word links to associate it with “Measure for Measure” and “Cymbeline” and even that it has stylistic references to the Sonnet Sequence.

Expert dating suggests that it was probably written some ten years before its publication. It clearly echoes elements of Samuel Daniel‘s “Delia” (1592) which was followed by “The Complaint of Rosamund”, Lodge’s “Phillis” (1593) which was followed by “The Tragical Complaint of Elstred”, and Spenser’s “Epithalamion” which was followed by his “Amoretti” (1595). All these poems share the attempt to resolve or disentangle the enigmas associated with love and lust in the Elizabethan era which “Venus & Adonis” as well as “Lucrece” are symptomatic. The choice of a partner, their social and personal attitude, their bearing and status in the relationship, their infidelity, betrayal and final abandonment were all part and parcel of failed Shakespearean romances. Today of course, when faced with similar dilemmas, we would more likely to turn to the advice given by some agony aunt in a national tabloid newspaper.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets (1609):

Here Shakespeare employs George Eld as printer with Thomas Thorpe as his publisher (so that he could use the TT encoding as a “red herring”, ie: Thomas Thorpe wrote the dedication?.) Where previously he employed Richard Field as printer and William Jaggard or John Harrison as publishers and subsequently Edmund Blount was designated by presumably the actors from the Globe theatre, John Heminges and Henry Condell as the publishers of the 1623 Folio although two of the sonnets were released and printed within a collection entitled “A Passionate Pilgrim” much earlier. I strongly suspect Heminges and Condell were merely “front-men” for this enterprise and that Lady Mary Pembroke was behind much of the financial and operational side of the publication. In this area of research Alexander Waugh (the grandson of the author Evelyn Waugh) has discovered various cryptic emblems or ‘hidden symbols’ (“The Sonnets Code Deciphered”) in the layout of Shakespeare’s title pages. Alexander Waugh thinks, and quite rightly that Dr. John Dee wrote the cipher code for Shakespeare’s Sonnets but it must have been the last thing he did secretly because he died in 1608. Through the use of sacred geometry, (a frequent approach by Freemasons to conceal a reference) it appears that an inverse pentagram can be deduced from the lines “SHAKES-PEARES” and “SONNETS” and from the letter ‘P’ in Shakespeares there is a further clue to the formation of an ancient Christian Greek Cross (Chiro) which was the inspiration for the first Christian Emperor, Constantine: “By this sign thou shalt conquer”.

The title page of Shakespeare’s Sonnets again features a header with the head of Dionysus with three fish hanging down and on either side with decorative foliage that mutates into the heads of two gargoyles facing inwardly towards Dionysus. Facing outward are two rabbits or hares and two winged cherubs facing inward leaning on the stem of a variety of flowers among which appear to be ‘forget-me-nots’. If the author had chosen symbolically to ditch the honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum-a solar symbol) in favour of forget-me-nots (Myosotis palustris) perhaps he might have feared being forgotten for whatever reason or in the face of his anonymity in the London theatrical milieu. On the issue of ‘Remembrance’ there is a scene in “Romeo & Juliet” where Juliet’s nurse mentions the plant rosemary and an exchange occurs between her and Romeo:

Nurse:

Doth not rosemary and Romeo begin both with a letter?

Romeo:

Ay, nurse; what of that? Both with an R.

Nurse:

Ah. Mocker! That’s the dog’s name; R is for

the–No; I know it begins with some other

letter:–and she hath the prettiest sententious of it,

of you and rosemary, that it would do you good

to hear it.

The word sententious means pompous moralising, so is Juliet’s nurse saying that Juliet, like the Virgin Queen Elizabeth, is hypocritical and unworthy of true love? Clearly, Romeo is an anagram of MOREO – or the surname Moore and if spelt without the double O merely ROME. One is also tempted to ask what letter could be substituted for the letter R? According to the nurse it is the so-called dog’s name (ie: r-r-r-r, the sound an angry dog makes when threatened or about to bite). Could the nurse be about to reveal the word POPE or possibly Prig? In fact because the sentence breaks off speculation runs riot as the names Robert Dudley, Robert Cecil, David Riccio (secret advisor/lover of “Mary Queen of Scots”) or King Richard II begins with an R, as well as Lady Penelope Rich, the supposed “Stella” of Sir Phillip Sidney’s poem. Or possibly even Richard Rich the prosecutor to Sir Thomas More who assisted in the dissolution of the monasteries.

Catalogue Page (1623 Folio of Plays):

Printed by William Jaggard and published by Edmund Blount and dedicated to the Earls of Pembroke (William Herbert) and Montgomery (Phillip Herbert) who probably financed its publication since it would have cost around £250 to produce the original 750 copies required for the first edition. The proof-reading, collating pagination and scribal reproduction would probably have involved Ben Jonson, Sir Francis Bacon and several other pen-men such as John Davies and took two years to complete. In the catalogue page of Shakespeare’s 1623 Folio of Plays the decorative header introduces several symbols and emblems that distinguish the author’s credentials to the “initiated and uninitiated” of London’s theatres. In the middle is an image of Dionysus, the patron of the Greek Mysteries in drama, music and ecstasy. In each hand he holds aloft two exotic birds (possibly peacocks or birds of paradise) and he is sat on a throne decorated with grapes (a sign of the Dionysian and Bacchic revels) and he is flanked on either side by two archers with lowered bows and arrows, taking aim and alongside them are two hares or rabbits perched on a plant, gazing outward and a strange-looking dog with antlers sniffing at the ground. Researchers from the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship have uncovered that the composite creature is a ‘Calgreyhound’, a medieval heraldic motif that usually has the head of a wildcat or lynx, the body of a deer, the forelegs of an eagle, the antlers or horns of an antelope and the hind-legs of an ox. It was known to be a unique heraldic motif on the coat of arms of the de Vere family from antiquity. A similar motif or emblem was employed on Thomas Watson’s “Hekatompathia” (published 1582) and is also found on the header of the plays “Othello” and “Measure for Measure”. Among the decorative motifs on either side of Dionysus are two 5-petalled flowers, possibly anemones, sacred to Adonis and the archers emerge out of a trumpet shaped flower with tendrils (possibly Honeysuckle). The hares or rabbits are puzzling but could be implied from the French, “Levre”, an animal of springtime or Easter which in effect is an anagram for de Vere’s surname, the honeysuckle is a floral symbol of the Sun as the plant follows in a spiral the course of the Sun as it grows. Its flowers are rich in a mellifluous nectar favoured by bees. Now most birds were generally an omen of the favour of the gods since they are the messengers of Heaven, in particular peacocks are sacred to the Greek Zeus (Jupiter) or as a hen to his wife (Juno). Their tails which resemble eyes are sacred to the insomniac Argos who held Io hostage and was finally lulled to sleep by Hermes who was able to sneak upon him and decapitate his all-seeing head. Archers, bows and arrows are synonymous with the power of thought and where it hits its target a sign that instantaneous clarity of mind is acquired. Directed downwards it is akin to the vengeful thunderbolt which outruns convention by throwing off earthbound limitations and in due course eliminating enemies.